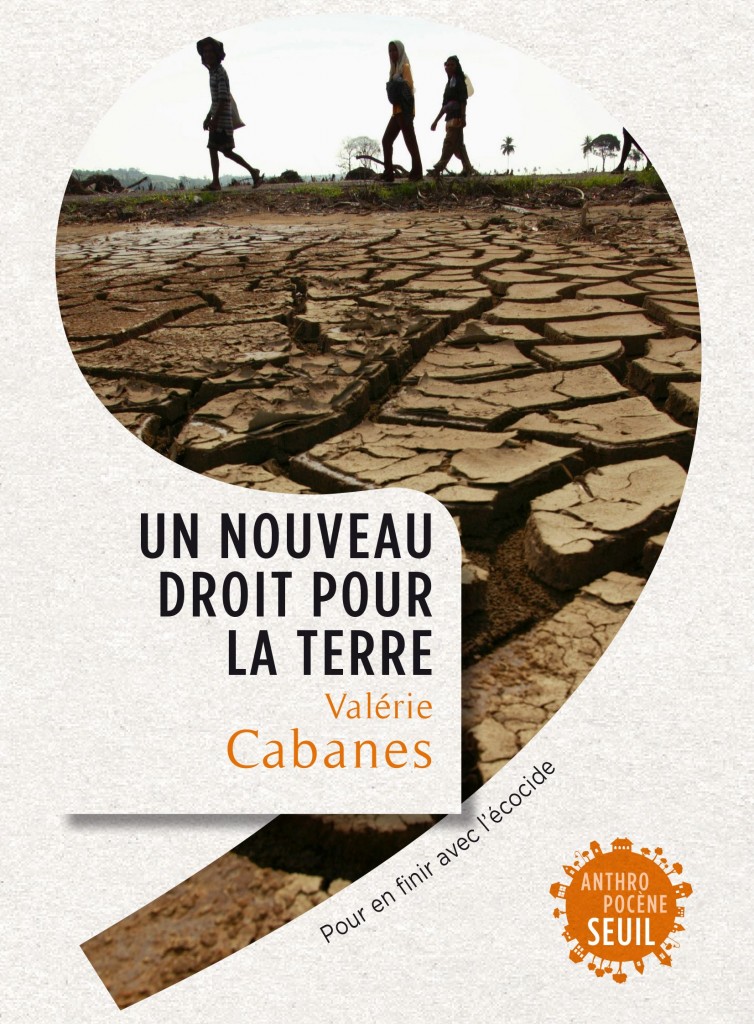

“If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear,” George Orwell wrote as a preface to his novel, Animal Farm.

This bit of wisdom seems like the sort of rallying cry that the founders of End Ecocide in Europe (Endecocide.eu) would have

come up with, had Orwell not preempted them. And even greater efforts will be needed in the near future to stop those profiteers who care nothing about the ecologies they decimate as long as their efforts show a profit. In fact, the more these mega-polluters despoil, the faster people who care about the Earth coalesce around a common goal, becoming a voice with which to be reckoned.

That voice has never been louder. Starting from modest beginnings – as a subject for debate by the United Nations (UN) International Law Commission – the End Ecocide movement gained a powerful, historical voice when, in 1970, a troubled Professor Arthur Galston proposed a “new international agreement to ban Ecocide”.

Galston, the inventor of Agent Orange, had an intimate knowledge of Ecocide. His formula would ultimately be responsible for the destruction of more than 5 million acres (2 million hectares) of what had previously been lush Vietnamese forests, pasture lands and mangrove swamps.

Nor did the destruction stop there. In time, this crime against the natural world would also spawn misfit children in the human world – children whose deformities not only prevented them from living a full life but, in many instances, prevented them from living at all.

Like J. Robert Oppenheimer, co-inventor of the atomic bomb which destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in WWII, Galston might have said of his invention: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” Instead, he proposed a new international agreement to ban Ecocide, which he defined as “the willful destruction of the environment”.

The Voices Gathered

But one voice is never enough, and in 1972 Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, delivering the inaugural speech to attendees at the UN Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment (later to become the UN Environment Programme, or UNEP), cited the ongoing war in Vietnam as an “outrage”.

The voices gathered. What had been a conversation became a chorus. Ecocide, which would soon garner the title of The Missing 5th Crime Against Peace, found more supporters. One, Richard Falk, Princeton University’s professor emeritus of international law, established the fact that intent was basically immaterial when it came to framing responsibility for environmental damage because most cases stemmed from either the profit motive or military advantage. This framework lent Falk’s 1973 Ecocide Convention draft policy even more authority.

By 1978, proponents wanted to add the Ecocide provision to the Genocide Convention, as well as the crime of cultural genocide, all under the ever-widening umbrella of Crimes Against Peace as cataloged by the 1985 Whitaker Report, which noted that special attention should be directed toward Ecocide, ethnocide and cultural genocide.

It came as no surprise to those working for legislation to curb Ecocide that, in 1990, Vietnam declared the wanton destruction of environment a domestic crime – as did nine other nations between 1990 and 2003.

Crimes Against Peace

The declarations were their only defense against nations who refused to see Ecocide – Article 26 – listed alongside the 1993 draft of four other Crimes Against Peace in the Rome Statute. Those four are: Crimes Against Humanity, Genocide, War Crimes, and Crimes of Aggression. All four were adopted in 1998, forming the working foundation for the International Criminal Court, or ICC, to handle these crimes from 2002 forward, when guidelines went into effect.

Which nations wanted Ecocide expunged from the document? The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States (or, according to other records, the U.S., France and Brazil). Whatever the reason behind the opposition, the powerful lobby of wealthy, mostly developed nations sent a clear message. Article 26, crimes against the environment, would require some loud shouting – virtually speaking – to ensure that Ecocide was not “disappeared” for lack of interest.

Or, as those who drafted the Ecocide Project noted: “Despite the overwhelming support for a law to prohibit Ecocide during war and peacetime, …the proposal was unilaterally removed overnight without record of why this occurred.”

We Choose Our Future

And why is it so important anyway? As Jared Diamond, author of Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed notes, we are on the same course as many historical societies which achieved prominence only to die off because they destroyed the very environment on which their lives depended. Mankind may use its technology to create artificial biomes, or even to voyage to new worlds, but it will never escape the natural world.

In 1994, Canadian-Australian lawyer Mark Gray published The international crime of Ecocide, which proposed such a law based on accepted international environmental and human rights statutes. As Gray opined, entities involved in harming the natural world on a gargantuan scale commit a dereliction of duty owed to humanity at large. In addition, where such omission or commission occurs, whether “deliberate, reckless or negligent”, it should rightly be identified as Ecocide.

Now, more than 50 years after the most egregious act of Ecocide in the 20th century, as Vietnam attempts to rebuild itself, international environmental lawyer Polly Higgins stands at the forefront of a movement which hopes to make Ecocide a crime.

Through her books, Eradicating Ecocide: Laws and Governance to Prevent the Destruction of our Planet (2010), and Earth is our Business: Changing the Rules of the Game (2012), Higgins hopes to see her proposal for criminalizing Ecocide (in Chapters 5 and 6 of the former) adopted by the United Nations.

Last year, a concept paper based on ideas from her books – and called the Law of Ecocide – was sent to the heads of all governments around the world. A presentation to jurists along similar lines was unveiled at the World Congress on Justice Governance and Law for Environmental Sustainability. This event took place before the Rio +20 Earth Summit.

In order to achieve sufficient relevance under the European Citizens’ Initiative to be heard by the European Commission, the End Ecocide in Europe movement requires 1 million signatures.

If the measure is subsequently passed into law, the Ecocide Directive would make it illegal for groups, enterprises or companies registered in the EU – as well as individuals representing such entities, whether at home or abroad\EU firms or those associated with same – to commit Ecocide, and the punishment would be commensurate with the crime.

About the Author:

Andrew Miller is a passionate member of the End Ecocide movement, an avid blogger, traveling enthusiast and co-founder of the tech startup scanandban.com.

0 Comments